Creativity is a Birthright (and a Habit?)

“Creativity is a habit and the best creativity is the result of good work habits.”

What makes some people more creative than others?

It's a question that spawned thousands of think pieces, articles, and blog posts and sparked conversations between strangers. Some believe that creativity is something that you are born with and uncover at some point. Others believe that creativity is a skill that you can acquire through sheer persistence.

What if it's both?

Everyone is born creative. Creativity is both a gift and an innate instinct that we all possess. To be able to create something out of nothing is unique and magic.

In his book The Creative Act: A Way of Being, Rick Rubin puts it this way: “Creativity is not a rare ability. It is not difficult to access. Creativity is a fundamental aspect of being human. It’s our birthright. And it’s for all of us. Creativity doesn’t exclusively relate to making art. We all engage in this act on a daily basis. To create is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before. It could be a conversation, the solution to a problem, a note to a friend, the rearrangement of furniture in a room, a new route home to avoid a traffic jam.”

We are all born with this ability, but creativity is also a muscle. And like all muscles, it must be flexed, stretched and strengthened to enjoy a full range of motion and harness its full potential.

Without consistent and intentional exercise, muscles weaken and become atrophied.

Doing creative things is hard, and learning to exercise it after letting it lie dormant is frustrating. Our creations may not match our aesthetic taste or vision for what we want to produce. At first, we will likely fail at finding the creative pursuit we enjoy. How many people have cameras collecting dust in a cupboard but eventually learn they have a flair for coding instead?

In the beginning, creativity is frustrating because we simply aren't that good at it yet.

But this resistance and frustration are necessary to reawaken and unlock creativity. We exercise this muscle through habitual experimentation, learning and failure. The best creative works (and creators) don't spontaneously appear from thin air; they result from jigsaw pieces coming together to create a complete picture. These are pieces like dedication, practice, life experience, following our curiosity, developing our taste, travelling, collecting, and connecting influences from unlikely places.

One of my favourite examples of this is Vincent Van Gogh.

Born in 1853 to a minister, father, and mother from a family of art dealers, Van Gogh grew up with an appreciation for the arts. At 16, Van Gogh worked as an art dealer at Goupil and Cie, learning about different artists, styles and movements. Afterwards, he worked as a missionary between 1878 and 1880. During this time, he studied religious texts and theology. He was exposed to the harsh living conditions and challenges miners and their families faced in the Borinage region of Belgium. Throughout these years, Van Gogh also worked as a teacher.

It was only at the age of twenty-seven that Van Gogh began painting and enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels.

We, of course, know him for his most famous paintings:

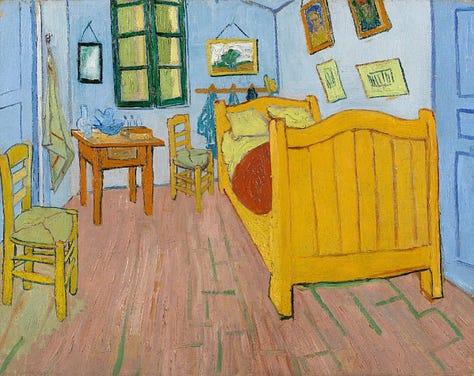

The Bedroom (1888)

Irises (1889)

Cafe Terrace at Night (1888)

Almond Blossom (1890)

Starry Night (1889)

The Sunflowers Series (1888-1889)

They are, of course, iconic and influential. But what we tend to overlook is that these paintings were not Van Gogh's first paintings. It took almost a decade of consistent learning and practice before he produced these works.

They result from Van Gogh's deep dedication to this craft, travel, consistent practice, learning from his contemporaries and drawing on his own lived experience. Over his lifetime, estimates reveal that Van Gogh produced more than 2,000 artworks, including 900 paintings and over 1000 drawings and sketches, and wrote hundreds of letters to his family and fellow artists.

Some of his earliest works, including The Potato Eaters (1885), represented scenes and vignettes of the working class, reflecting his time spent in Belgium. His use of colour, form and subject matter was inspired by Japanese art, woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e and the Japonisme movement. His particular style of art and techniques were inspired by Impressionists, whom he spent time with and regularly kept in contact with.

During art school, Van Gogh struggled with traditional academic training, experienced conflict with his instructors, struggled with figure drawing and felt a lack of appreciation for his work. Had he quit during his early years, we may never have been able to experience his art.

What strikes me about Van Gogh's life is that he was intentional about learning the art of painting and obsessed with learning how to be a better artist. His most profound works came later in his life, after years of practice, experimentation and failure.

This is where the problem lies with creativity. We tend to overlook the work and the circumstances that lead to incredible breakthroughs or creations.

We believe that we must not be cut out for creative pursuits because we are not immediately producing works of profound art and significance that match our taste. We compare our work with those who have been honing their craft and building their muscle for months, years, and maybe even decades more than we have. But as with many things worth learning, creativity requires habit, dedication and persistence to yield results.

Nobody articulates this better than Ira Glass, a prominent American radio personality, host, producer, and podcaster:

"For the first couple years you make stuff, it's just not that good. It's trying to be good, it has potential, but it's not…

A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn't have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this.

And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know its normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions."

Confidence, self-belief and unleashing our full creative potential comes when we believe we have the ability to do difficult things and create what we envision. If we continue to work on these creative habits, make time for creative pursuits, and find joy in the craft and the process of creating, we may not reach the heights of Van Gogh, but the day will come when our technical skill matches our taste. We can produce work that we are proud of.

That work might be a painting or a piece of writing. It might be a poem or a video game. It could be a robot or a community tattoo studio. It could be an app or a clothing brand. Whatever it is, it will come through flexing that creative muscle.

The takeaway is this: what determines a person's creativity isn't innate talent or instincts – after all, we are all born creative. To truly unlock your full creative potential, creativity must be turned into a habit and into a way of being rather than a simple output.

Twyla Tharp – an American dancer, author of The Creative Habit, and choreographer – once said: "Creativity is a habit, and the best creativity is the result of good work habits."